The Tree Collectors: Reuben Paterson

"Reuben Paterson stages encounters meant to be felt. To look is to be looked at, to desire is to be unsettled, to touch is to risk breaking. The works exist in relation, insisting that we too are multiple, that we too hold contradictions. They remind us that beauty can overwhelm, that desire can be a form of thought. They ask us to project ourselves into the cosmos, to imagine what cannot yet be seen, to grant emotional interiority to stars and exoplanets as sites of possibility, places where life might exist or begin anew. In doing so, they open questions about Earth’s future, the continuation of our species, and the ways we imagine life beyond our world."

Excerpt from Dina Jezdić's essay Leap of Faith. The full version can be read below.

-

Reuben Paterson, The Revivalist (Constellation Pavo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, The Revivalist (Constellation Pavo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, The Ever Free (Constellation Pavo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, The Ever Free (Constellation Pavo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, I Think I Told You Before That They Don't Own Me (Constellation Leo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, I Think I Told You Before That They Don't Own Me (Constellation Leo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, I Stretched Some String from Steeple to Steeple (Constellation Pavo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, I Stretched Some String from Steeple to Steeple (Constellation Pavo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, How Slow the Wind (Constellation Matariki), 2025

Reuben Paterson, How Slow the Wind (Constellation Matariki), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, One Beautiful Morning, in the Land of a Very Gentle People (Meteors Delta Aquariids, late July 28, 2025), 2025

Reuben Paterson, One Beautiful Morning, in the Land of a Very Gentle People (Meteors Delta Aquariids, late July 28, 2025), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Lava Lamp (Constellation Pavo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, Lava Lamp (Constellation Pavo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, My Room Lights Up (Meteor Fireball, July 12, 2025), 2025

Reuben Paterson, My Room Lights Up (Meteor Fireball, July 12, 2025), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Because I Want to Move into You, 2025

Reuben Paterson, Because I Want to Move into You, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, How Slow the Sea (Constellation Matariki), 2025

Reuben Paterson, How Slow the Sea (Constellation Matariki), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, I Stretched Some Small Gold Chain from Star to Window (Constellation Pavo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, I Stretched Some Small Gold Chain from Star to Window (Constellation Pavo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Be the Person Your Dog Thinks You Are (Constellation Lupus), 2025

Reuben Paterson, Be the Person Your Dog Thinks You Are (Constellation Lupus), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, The Context, 2025

Reuben Paterson, The Context, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Unconditional (Constellation Pavo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, Unconditional (Constellation Pavo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, What Mature Men, 2025

Reuben Paterson, What Mature Men, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, So Why Don't You Move into Me, 2025

Reuben Paterson, So Why Don't You Move into Me, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, I Wish You Could See Me from These Heights (Constellation Pavo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, I Wish You Could See Me from These Heights (Constellation Pavo), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Could That Be Us, 2025

Reuben Paterson, Could That Be Us, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Let God Sort 'em Out, 2025

Reuben Paterson, Let God Sort 'em Out, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Miss Fingered 44 (Atlas Comet C/2024 G3, January 2025), 2025

Reuben Paterson, Miss Fingered 44 (Atlas Comet C/2024 G3, January 2025), 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, One More Night (Constellation Leo), 2025

Reuben Paterson, One More Night (Constellation Leo), 2025

Leap of Faith

Text by Dina Jezdić

Walking into Reuben Paterson’s Brooklyn studio, I am seized by a sudden, visceral jolt. It is the kind of vertigo that rises when the body senses its own alertness, the queasy thrill of being pulled into the orbit of an artwork. The paintings I face draw me in with a charged intensity, their presence both magnetic and elusive, holding me within their gravity. They recall the astonishment of looking up at the night sky, and the strange awareness that the light reaching our eyes has already travelled across time, from moments that no longer exist. The Tree Collectors turns this sensation into metaphor: to paint a forest is to admit you cannot see it all at once, just as the stars are remnants of another time, flickers from vanished moments still arriving here. To look is already to believe — to trust that the cosmos holds us, that some order exists within the vastness, that meaning lies just beyond what is visible. For centuries, people have tilted their heads back to ask the unanswerable: Where did we come from? What lies beyond the horizon? How can infinity be measured? These are questions not of science but of faith — faith that the darkness is not empty, and that what it holds will matter when it comes into view.

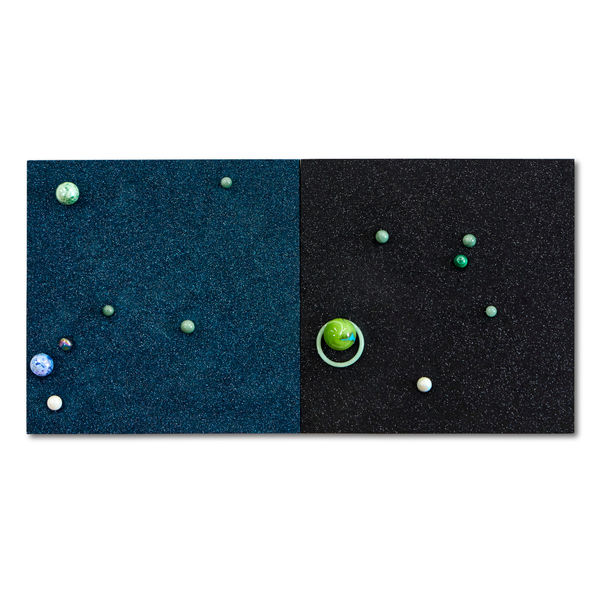

Within Reuben Paterson’s new body of paintings lives what Søren Kierkegaard once described as a “leap of faith.” Though Kierkegaard spoke of religion, the idea belongs to many parts of life: it is what happens when we step beyond certainty into the unknown, when we begin a new chapter, place our trust in another person, or follow an intuition that reason cannot yet explain. The leap is powerful because it asks us to set aside the shelter of logic and give ourselves over to trust. Paterson paints from that threshold. Each canvas begins with a celestial chart, like a guide carrying him with confidence that the process will hold, and that intuition will steady the hand. In his studio, glitter, marbles, glass orbs, pearls, obsidian, resin, and paint become telescopes of another kind. They conjure the sensation of standing beneath the stars, that mingling of beauty and smallness, the reminder of our fragility and of the immensity of the unknown.

NASA’s James Webb telescope, launched into space to orbit far beyond Earth, works in this way, capturing infrared light that has travelled across the universe, reaching from a time long before Earth or the solar system existed. This cosmic time machine, can detect the faint heat of distant exoplanets and glimpse the first galaxies that ever formed, revealing a past more than thirteen billion years old, folding past, present, and future into a single luminous instant. Paterson’s paintings dwell in this register. Their glittering surfaces refuse the straight line of chronology. They are not narratives with beginnings and endings but open fields that can be entered at any point. To look at them is to be both here and elsewhere, now and then. They carry the sense of Te Ao Māori time as a spiralling continuum, an understanding that we live within overlapping layers where the past and the future touch in the present.

Desire in these works is layered and complex. The painted eyes invite, seduce, even cruise, yet they also hold the viewer at a distance. They are strong and upright, masculine in stance, yet softened in embrace and feminised in gesture. This refusal of singularity is the artist’s radical proposition: masculine aesthetics are queered and feminised, while feminine softness is granted structural force. The works exist in the space between looking and being looked at. The paintings hold us in their gaze as much as we hold them in ours, and in that exchange, desire becomes a way of thinking. The result is a new genealogy, one that insists on multiplicity.

Caught off guard, my eyes met the tiger in I Think I Told You Before That They Don’t Own Me (Constellation Leo). Upright, embracing the tree, their gaze held me with a tenderness that was also commanding. I felt a jolt of arousal. It is rare, perhaps almost taboo, to admit being turned on by painting. Yet that moment felt electric. It revealed the radical intimacy of Paterson’s work: the way it holds multiplicity, allowing contradictions to coexist. The erotic here extends beyond sex. It encompasses longing, absence, tenderness, and the piercing vulnerability of being seen, by art itself.

This doubleness between the monumental and the intimate is one of the artist’s key achievements. The paintings are both armour and skin, both shield and lure. Pearls stud the surfaces, forming constellations that glitter with tenderness and depth. Marbles roll across the canvases, bringing play into the gallery. They recall childhood games, the clack and roll of objects in motion, while also evoking planets, orbits, and the sweep of cosmic scales. Resin pools at the edges, forming cracked crusts like sand drying at the shoreline and planetary skins, imagined. All this alchemy makes the surfaces gleam, and it is precisely this abundance that becomes beautiful. Their planetary shimmer exists alongside their fragility. Glass orbs appear as if they could slip away, shatter, and roll across the floor, lost forever. This fragility matters. It reminds us that permanence is an illusion.

Reuben Paterson stages encounters meant to be felt. To look is to be looked at, to desire is to be unsettled, to touch is to risk breaking. The works exist in relation, insisting that we too are multiple, that we too hold contradictions. They remind us that beauty can overwhelm, that desire can be a form of thought. They ask us to project ourselves into the cosmos, to imagine what cannot yet be seen, to grant emotional interiority to stars and exoplanets as sites of possibility, places where life might exist or begin anew. In doing so, they open questions about Earth’s future, the continuation of our species, and the ways we imagine life beyond our world. They remind us that our need to believe—in machines, in the heavens, in art, in the human heart—is a need for connection. It is the leap required to surrender and to paint a forest without knowing where the path will lead.

Belief, in this vision, is openness. It is trusting that art is not only something we see. It is something that sees us in return.