How to Disappear: Steve Carr

In How to Disappear, Steve Carr leans deeper into his enduring role as the comic outsider, part magician, part sad clown, pursuing vanishing acts that never quite succeed. Across film, sculpture, and photography, Carr stages a series of near-escapes: crouched behind lenticular plastic, lost in coloured smoke, or swallowed by a moving bush. Each attempt is earnest, absurd, and knowingly doomed.

Drawing on a legacy of physical comedy from Chaplin to Three Amigos, Carr’s work embraces failure as a kind of truth. His silent protagonists, dressed in dad jeans and awkward disguises, aren’t heroes or alphas. They fumble, hide, and try again. Beneath the humour lies something more tender: a longing for transformation, transcendence, or simply a moment of reprieve from being seen.

Here, camouflage becomes costume, and disappearance becomes performance. A figure tries to merge with the landscape but never fully escapes it. Whether casting abandoned dog-poo bags in bronze or turning his own legs into a lamp, Carr shows us that even in the act of trying to disappear, something of us always remains - half-visible, gently ridiculous, and strangely moving.

The essay Dad Jeans by Anthony Byrt accompanies the exhibition and can be read below.

-

Steve Carr, Bush Lamp, 2025

Steve Carr, Bush Lamp, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Many Steves, 2025

Steve Carr, Many Steves, 2025 -

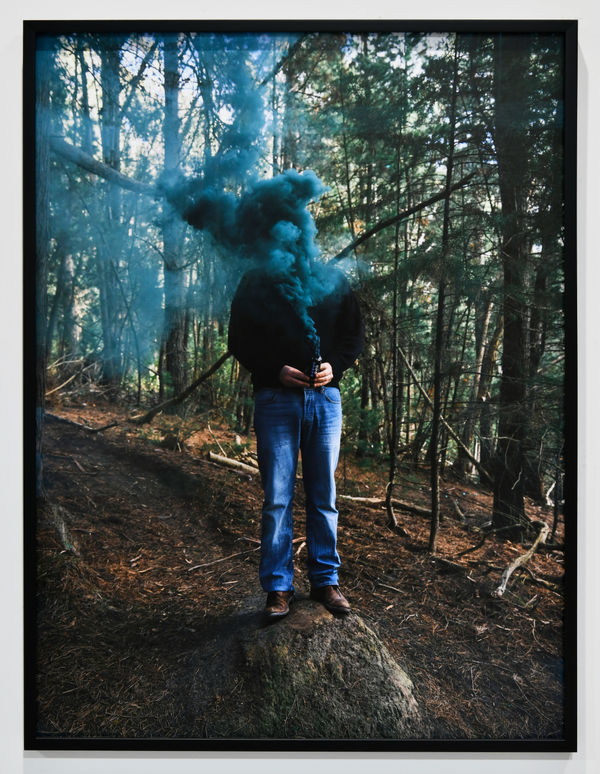

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 1, 2025

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 1, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 2, 2025

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 2, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 3, 2025

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 3, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 4, 2025

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 4, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 5, 2025

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 5, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 6, 2025

Steve Carr, Smoke Clouds 6, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 1, 2025

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 1, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 2, 2025

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 2, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 3, 2025

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 3, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 4, 2025

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 4, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 5, 2025

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 5, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 6, 2025

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 6, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 7, 2025

Steve Carr, Standing Bush 7, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Creeping Bush, 2025

Steve Carr, Creeping Bush, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Doggie Poo Bag, 2025

Steve Carr, Doggie Poo Bag, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Invisible Man, 2025

Steve Carr, Invisible Man, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 1, 2025

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 1, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 2, 2025

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 2, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 3, 2025

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 3, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 4, 2025

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 4, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 5, 2025

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 5, 2025 -

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 6, 2025

Steve Carr, Invisibility Shields 6, 2025

Dad Jeans

Essay by Anthony Byrt

There is a sequence in one of Charlie Chaplin’s best silent films, Shoulder Arms, 1918, in which the great physical comedian disguises himself as a tree. Set in the trenches of France during the Great War, Chaplin plays a soldier trying to mask his bumbling cowardice behind acts of bravado. When his commanding officer calls for volunteers for an as-yet-unexplained mission, all of the men throw their hands up, and Chaplin is picked. He puffs out his chest and casts a mocking glance at his fellow soldiers, just as the officer tells him that he may not return alive. His chest instantly collapses; the fear on his face is comically obvious. We next see him behind enemy lines in his ridiculous tree suit, stomping around clumsily on trunk legs, trying not to be detected. Predictably, he fails, spotted by a fat German soldier. He heads for the protection of the forest, where his pursuer bayonets random tree trunks, hoping to skewer his man. Chaplin escapes, and stumbles to victory—capturing, despite his haplessness, the German Kaiser, and picking up a beautiful French love interest along the way.

Shoulder Arms was one of Chaplin’s early successes, a box office smash built upon a perverse conceit—that a war so present, and responsible for so much slaughter, could be laughed at. His masterstroke was to cast himself not as a great war hero but as a coward: a man whose fears, combined with his physical shortcomings and ludicrous good luck, inadvertently lead him to glory. The plot plugs into a long comedic history: Chaplin was the first great filmic embodiment of the Fool, a tradition which extends back thousands of years through vaudeville, the Commedia dell’arte and Shakespeare, through court jesters, all the way to Greek theatre. The Fool’s sustainability is predicated on the inexhaustible reservoir of male failure, and the failing male body: sexual dysfunction, weakness, cowardice and uncoordination never—from a comedy perspective, at least—get tired.

Since the early 2000s, Steve Carr has consistently played the Fool in his art, and he owes much to the legacy of Chaplin’s silent buffooneries: a young Steve playing air guitar to Joe Satriani, acting out his sad stadium fantasies alone; Steve performing a table cloth pull that ends in predictable disaster; Steve sitting in a spa pool filled with beautiful women, awkwardly sipping beer. Even when he’s not there, there’s Big Sad Energy on display, as in Burnout, 2009, in which a solitary driver fills the early-morning West Auckland sky with tyre smoke, for an audience of no one. Over a quarter-century of video art, Carr’s protagonists have never uttered a word, relying instead on banal and often deeply stupid physical acts. But often, those acts transcend their comic ubiquity and enter a realm of magical transformation. In Splash, 2007, we watch a surface of Hockney-blue water—a video-as-painting—suddenly broken by Steve doing a bomb, then coming up for air. And in Screenshots, 2011, a magician’s hands (they might be Steve’s, but it doesn’t really matter) prick paint-filled balloons in ultra slow-motion, each rubber skin peeling back under the pin’s pressure to briefly reveal a swollen gland of still-formed colour, before it blows apart in a sticky mess.

Carr was absent from his work for several years, but he’s recently made a midlife return. In Sneaking Bush, he enacts an archetypal cartoon scenario, his denim-clad legs carrying around a bush that obscures the top half of his body. When he kneels down, his dad jeans—carefully chosen faded 501s—disappear: a perfect forest disguise as he surreptitiously works his way between Queenstown pines. Without an antagonist or clear plot, we don’t know whether Steve-as-bush is hunter or hunted; hiding because he fears for his safety, or simply because he’s a creep. Either way, the costume makes for a dazzling magic trick: the vanishing, when he drops to the ground, is total.

Invisibility Shield involves a less convincing disguise. As the work opens, we clearly see Carr’s arms holding a sheet of lenticular plastic, his grey hair striking out above it, the rest of his body crouched awkwardly behind. A patch of the plastic fogs with his breath; he moves his head so the moisture doesn’t obscure his view through the sheet. He’s looking at, or for, something. It’s a bit sad to watch, as Carr keeps adjusting his position, obviously in discomfort from the effort of staying behind his shield. In its first minute or so, it seems like a phenomenally pointless performance—he’s doing a terrible job of hiding, and there is neither obvious purpose nor target. It also, at times, feels sadistic, as he contorts his late-forties body into oddly fetishistic poses, down on one knee, the opposite elbow pointing upwards in a painful-looking clench. But over time, it turns into a feat of empathetic endurance—you can feel the pins-and-needles—and the shield becomes more cocoon than camouflage. This is Carr, alone in the woods, trying to squeeze himself inside a box. He is in pursuit of a pure physical experience; he is trying to disappear.

He is, of course, doomed to fail—but this impulse towards self-erasure is a deep and archetypal one. All great religions promise the nirvana of submission, which followers can reach through commitment and repetition. In contemporary secular life, oblivion is chased through other means: drink, sex, drugs, meditation, ultra-marathon running. Whatever the mechanism, the motivation is the same—to escape the self and give over to something beyond the regular limits of our control. This search for a similar profundity in Carr’s work isn’t a stretch, I don’t think, because it exists as an ever-present tension: a sense that behind the corny jokes and dumb physicality, there is always a pursuit of physical release and transcendence. The fact he rarely achieves it, or that his desired result can be so unclear, doesn’t change that fact that he wants it—whatever ‘it’ is—very badly. Failure is part of the structure of comedy. But it is also part of the structure of life, which is why we can empathise so strongly with Carr’s quiet disasters.

*

Comedians always look to squeeze every bit of value out of their best gags, and Carr is no different. Once he realised he was on to a winner with the sneaking bush, he rolled it out in a series of photographs, presenting his bushman in the sublime hills of Queenstown, not so much blending in with the forest as posing amidst its glory—glossy-green selfies whose nature-state is almost complete, but for those ill-fitting jeans. The light in the images is slanting and beautiful; sky and lake are the same pale-blue as his denim. He is an interloper, but in another sense, Steve-as-bush is no more alien or invasive than the trees around him—the commoditised, low-value pines that have been planted all over the country, delivering near-endless disappointment to investors and causing more ecological damage than they’re worth.

He does the same with his invisibility shield, although these photographs have a more painterly dimension. In still form, the lenticular plastic becomes more effective: Steve is far harder to make out, and instead, his features melt into a Richter-like streaky blur, the shield-as-frame held up by a pair of creepy knitted mittens (I am revealing my own anxieties now—I have always found mittens upsetting accessories; flipper-gloves that turn our digital dexterity into something cartoonish and animal). And in a separate series of photographs, Carr lets off brightly coloured flares, which similarly hide his upper-half—the smoke to his shield’s mirror. While this is an act of disappearance, it is also a gesture of panicked visibility. Steve can’t be in any real danger; he’s barely off the mountain-bike track. Instead the flares become beautiful, painterly interventions, a way to leave his silent and temporary mark on the landscape.

Doubling down, then, on the doubles. The army of half-present (or half-absent) Steves is overwhelming, a feeling of viral multiplication that Many Steves exacerbates. Five identical figures in those same jeans and wearing high-vis tops partially hide themselves behind pine trunks. Each figure protrudes just enough that they take on a fungal quality—giant, sneaky man-mushrooms spawning on the trees. The real Steve, of course, will not reveal himself, because he is all of them, all at once. And, not quite done with himself, Carr has made a lifesized doppelganger: legs carved from the same wood surrounding him then painted denim-blue and mounted with his bush disguise, turned into a standing lamp—a half-hidden Stranger destined for the corner of a suburban living room.

*

In a recent conversation, Carr reminded me of the brilliant ‘singing bush’ sequence in the 1986 comedy Three Amigos. The three idiots of the film’s title, played by Steve Martin, Chevy Chase and Martin Short, approach a clearing in search of the mythical singing bush. In front of them, belting out ‘She’ll be Comin’ Round the Mountain’, is what could only be the bush they’re seeking. But after they politely enquire as to the bush’s identity and don’t receive an answer (because it won’t stop singing), they decide it must not be the singing bush after all. Instead, they try to summon a different mythical guide, The Invisible Swordsman, with absurd incantations. They almost succeed, until Chase’s character accidentally shoots the invisible man, who falls to the dusty ground with an unseen thud.

Three Amigos owes a huge debt to Chaplin. Set in the early twentieth century, the film’s protagonists are silent movie stars. Dropped by their studio, they take up an invitation from a fan in Mexico who is convinced the on-screen heroes can save her village from bandits—not realising that they are, in fact, real-life cowards. This figure of The Coward was a dopey Hollywood stalwart for generations, but it has faded from view recently, drowned out by the rise of ‘alpha’ and ‘sigma’ masculinity online and in popular culture. The traits of the alpha are obvious, and everywhere, from the toxic musings of Andrew Tate, to the rise and rise of the UFC, to the misogynistic narratives that have seen millions of men—young men in particular—embrace far-right ideologies. The sigma persona is more ambiguous, but just as pernicious: the outsider who supposedly doesn’t give a fuck about rules and moves through society to the beat of his own tune—think John Wick, or Peaky Blinders’ Tommy Shelby. In his excellent article ‘The sad, stupid rise of the sigma male’, Guardian writer Steve Rose parodies the figure perfectly. ‘You are a lone wolf’, he writes:

You are an independent thinker who makes his own rules. You are confident and competent. Women are drawn to you, but you don’t really care about them. Your day begins at 4.30am with a cold shower, followed by a punishing workout and an even more punishing skincare routine. You shun conventional career paths and run your own business, probably in crypto or real estate or vigilante crime fighting. You are that rarest of males – you are a sigma.

Wellness influencers and muscle-bound mountain-runners have tried to turn nature into a platform for that same ultra-masculinity; yet another thing to be conquered through strength. In a final reminder of the inevitable failure of these Man Alone fantasies, Carr has cast a series of doggie-poo bags in bronze, his editions an identical, lurid green to those abandoned and lumpy sacks that some dog-walkers (Carr has always been a committed, loving and very responsible dog owner) leave abandoned on trails or tied in tree branches like disgusting Christmas baubles. These bags break the illusion of our solitude in nature, reminding us that we can never truly get away from each other, or each other’s waste. Carr’s magic is to turn the bags’ temporal bleakness into something beautiful and permanent: rock-solid memento mori. They are also the last resort of the ailing comedian—the poo joke.

Carr’s sad comics, wandering the woods in their Scooby Doo disguises or scooping up after their canine companions, are anything but sigmas. Instead of fear and awe, they evoke a mix of sympathy and parody, exhibiting a version of midlife behaviour we can all recognise and roll our eyes about, and yet we continue to accept it, and never quite let ourselves fully look away. As is so often the case in Carr’s work, these figures are also magicians, drawing our attention to the magic of material transformation. Elements can exist as liquid, solid, and gas. In Carr’s new work, processed and fabricated materials—plastic, coloured smoke, denim, dogshit—are turned into bronze, wood, photographic prints, moving light thrown onto a wall. When each change is encountered there is a pause, and a wobble: not just a moment to laugh at Steve, but a second to wonder at how he’s done the trick, and, in his sublime and vulnerable loneliness, why.

When things feel so bleak, it’s also good to remember that cultures can transform too. On a recent shopping trip with my 14-year-old son, I saw with a shock that 501s were back, a Levi’s store filled with giant banners for them. Maybe, I thought, we do still need dad jeans, and the anti-heroes who bravely move through our dangerous world wearing them.