In that stone, in that cyclone, in that leaf: Group Exhibition

-

John Pule, Seven Days, 2012

John Pule, Seven Days, 2012 -

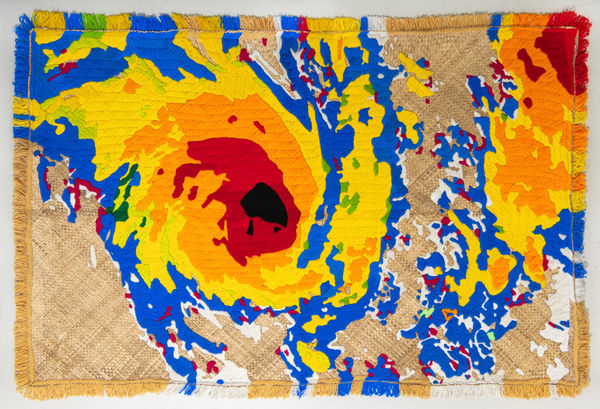

Yuki Kihara, Heta, 2025

Yuki Kihara, Heta, 2025 -

Brett Graham, 34.04 N 118.52 W, 2024

Brett Graham, 34.04 N 118.52 W, 2024 -

Yuki Kihara, Olaf, 2025

Yuki Kihara, Olaf, 2025 -

John Pule, I Kneel, 2017

John Pule, I Kneel, 2017 -

Shane Cotton, Super Radiance, 2024

Shane Cotton, Super Radiance, 2024 -

Emily Karaka, Pepeha, 2021

Emily Karaka, Pepeha, 2021 -

Yuki Kihara, Evan, 2025

Yuki Kihara, Evan, 2025 -

Patricia Piccinini, The Sage, 2025

Patricia Piccinini, The Sage, 2025 -

Emily Karaka, Tears over Tamaki Makaurau, 2025

Emily Karaka, Tears over Tamaki Makaurau, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Te Haerenga o Matariki: The Journey of Matariki (Constellation Taurus), 2025

Reuben Paterson, Te Haerenga o Matariki: The Journey of Matariki (Constellation Taurus), 2025 -

Colin McCahon, We are the Hull of a Great Canoe, 1969

Colin McCahon, We are the Hull of a Great Canoe, 1969 -

Yuki Kihara, Pola, 2025

Yuki Kihara, Pola, 2025 -

Reuben Paterson, Respect Them For Who They Are (Alpha Centaurids Meteor Shower, February 6, Waitangi Day, 2025), 2025

Reuben Paterson, Respect Them For Who They Are (Alpha Centaurids Meteor Shower, February 6, Waitangi Day, 2025), 2025 -

Star Gossage, Kia Mau ki te Mātauranga ō tō Wahi / Hold Fast to the Knowledge of your Place, 2025

Star Gossage, Kia Mau ki te Mātauranga ō tō Wahi / Hold Fast to the Knowledge of your Place, 2025 -

Emily Karaka, Rahui at Taurarua: Kaitiaki at Mataharehare, 2021

Emily Karaka, Rahui at Taurarua: Kaitiaki at Mataharehare, 2021

We sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood

- Teresia Teaiwa

Earlier this year, wildfires rocked the Greater Los Angeles area, destroying thousands of buildings and burning over 50,000 acres. Extreme weather events – cyclones, rainstorms and floods – are increasing with the impacts of climate change, which pose a very real threat for Pacific nations. This exhibition, In that stone, in that cyclone, in that leaf, brings together a group of artists whose practices explore and expand contemporary perspectives on place, identity and environmental concerns in Aotearoa and Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa. It features the work of represented artists Shane Cotton, Brett Graham, Reuben Paterson, Patricia Piccinini, John Pule and John Walsh, with invited artists Star Gossage, Emily Karaka and Yuki Kihara, and the late influential painter Colin McCahon (1919-1987).

We live in an extraordinary part of the world. We are surrounded by ocean, which guides and sustains us, shapes belief systems, is a platform for exchange and encounter and is deeply connected to our relationship with the land. The environment feeds into our visual culture with vitality and urgency, which is explored in different ways throughout this exhibition, contributing to an understanding of who we are and the challenges we face. The title of the show comes from a poem by John Pule (Niue), which reads ‘I see my love for this world in that stone / in that cyclone in that leaf.’ It captures the sense of an environment with which we are deeply interconnected. Another poem by Pule reads, ‘I kneel / cup my hands / to drink seawater/ instantly feel / my genealogy.’

Three major new works in the exhibition by Yuki Kihara (Japan, Sāmoa) form part of a recent series titled Tala o le tau: Stories from the weather. These large scale embroideries on pandanus mats were created in collaboration with the Moata'a Aualuma Community, a women's group in the village of Moata'a on Upolu Island, Sāmoa. The works chronical tropical cyclones that have directly and indirectly impacted the Sāmoan archipelago over the past two decades. Kihara has utilised infrared satellite imagery, capturing temperature and movement of tropical cyclones across the region and transformed it into a vibrant, urgent call to action for their island community, which is profoundly susceptible to the impacts of climate change.

The work 34.04 N 118.52 W by Brett Graham (Ngāti Koroki Kahukura, Tainui) forms part of an ongoing series Graham commenced in 2012 titled Tangaroa piri whare. The series takes its name from the Māori expression that describes the omnipresent power of the sea. Legend tells that Tangaroa, god of the sea, was the first to create a Māori carving, abducting Manuruhi, son of Ruatepupuke, and transforming him into a wood carving to adorn his house beneath the sea. The works make tribute to Tangaroa in different ways, reflecting upon his mana and ability to shape and transform our world on both land and sea. Recent works in the series have focused on sites of trauma on the planet, where the lines converge on a specific point, the ‘ground zero’ of impact. 34.04 N 118.52 W refers to the recent devastating fires in Los Angeles. In each work, Graham’s carvings resemble a shield, a form of protection, real or imaginary, with which to avert disaster, malevolence, and misunderstandings.

The work of Emily Karaka (Ngāpuhi, Waikato-Tainui, Ngāti Ruanui) is grounded in the cultural landscape of Aotearoa, traversing the political and the personal. Her work Pepeha, 2021 is a powerful representation of her connection to land and identity, utilising text as a direct means of communication. The work was inspired by the popular band Six60’s bilingual waiata Pepeha, the lyrics of which read Ko Mana tōku maunga / Ko Aroha te moana / Ko Whānau tōku waka/ Ko au e tū atu nei / Mana is my mountain / And Aroha is my sea / Whānau is my waka / And all of that is me. It was originally exhibited in Puhi Ariki, the opening exhibition of the Wairau Māori Art Gallery in Whangarei, 2022. Rahui at Taurarua: Kaitiaki at Mataharehare refers to the protest over the proposed Erebus memorial at the Parnell Rose Gardens, a culturally significant site with a sprawling, sacred pōhutukawa. Karaka’s three works in this exhibition explore concepts of legacy (Pepeha), place (Rahui at Taurarua: Kaitiaki at Mataharehare) and belonging (Tears over Tamakimakaurau).

Colin McCahon’s painting We are the Hull of a Great Canoe is the earliest in the exhibition. Painted in 1969, the text ‘E KORE E NGARO HE TAKERE WAKA NUI / we will never be lost; we are the hull of a great canoe’ is taken from the book The Tail of the Fish: Māori Memories of the Far North by Matire Kereama, which was published the year prior and was given to McCahon by his daughter Catherine. As a Pākehā, McCahon’s use of te reo Māori continues to be a topic of debate to this day. McCahon showed a revitalized interest in te ao Māori in 1969, which many have attributed in part to the birth of his mokopuna, his daughter Victoria and husband Ken Carr’s first-born child. This work talks to the ancestral waka which tie Māori both to other Māori descendants, and to the wider Te Moana nui-a-Kiwa.

Wellesley Gallery

The work of Star Gossage (Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Ruanui) is emotive and ethereal. Gossage lives and works on ancestral land in Pākiri, northeast of Auckland. There is an immediacy to Gossage’s use of line and brush, while her layered combinations of colour seem to defy definitions of time. Figures that occupy her landscapes are deeply connected to the whenua, whānau, and wairua of place. At times barely indistinguishable from their surroundings, they often appear as though tūpuna / ancestors. Recently, Gossage travelled to Tahiti, which influenced subsequent work. She comments, “Fiji, Vanuatu, Hawaii, Rarotonga, Tahiti. Whenever I travel in the Pacific I have the same feelings in my heart – feelings of manaaki, aroha and whanaungatanga for the people and their lands.”

Works by gallery represented artists further contribute to narratives of place, identity and environmental concerns. Australian artist Patricia Piccinini’s hybrid The Sage is a cross between the Norfolk Island boobook owl, a species that now only exists as a genetic hybrid, and a complex consumer object. Piccinini comments, “I am returning to a very personal hybridity that I have explored for many years, merging organic creatures and bodies with entirely artificial objects…we find birds – representing freedom, optimism, resilience – intermingling with another long-held fascination of mine: shoes.” In the 1980s only a single female Norfolk Island boobook owl remained, its decline in large part due to deforestation. Two New Zealand morepork were introduced as mates, and now a small hybrid population exists on the island. Here, Piccinini’s brightly coloured Sage is hyperreal, with synthetic textures and folds. It looks upwards with a sense of wonder, or bewilderment. Piccinini’s practice explores ideas of bio-technical intervention. Questions of scientific progress and ethics are intertwined, as are ideas of care and connection. With a distinct material sensibility, Piccinini questions our understanding of set relationships in the world.

Hybrids, in other forms, are also apparent in the work of John Walsh (Te Aitanga a Hauiti, Ireland) and John Pule. In Walsh’s painting Marakihau, a mythical being soars above an endless sea. In te ao Māori, a marakihau is considered to be a taniwha, a supernatural sea creature or spirit whom some believe represent tūpuna that have taken up residence in the sea. Walsh’s work is an amalgamation of abstract and figurative painting, that questions how we might navigate the future. John Pule’s painting Seven Days features hybrid creatures that make reference to Polynesian deities. Structurally the work bears resemblance to Niuean hiapo traditions, while Pule’s lexicon of imagery is a visual language that incorporates stories of migration, colonial conflict and exchange.

A questioning of bicultural identity, and our collective cultural identity is at the heart of Shane Cotton’s practice (Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Hine and Te Uri Taniwha). The painting Super Radiance formed part of Cotton's recent exhibition New Painting, which delved into the collision of Indigenous and European time systems, warping time, memory, and nature through the lens of his Ngāpuhi whakapapa. The works place ancestral figures in surreal, cosmic landscapes, exploring hybridities, transformation, and the cyclical nature of history. Cotton’s paintings blend history, mythology, and technicolour imagery, reflecting on the layered, nonlinear relationship between the past, present, and future in Aotearoa.

The work of Reuben Paterson (Ngāti Rangitihi, Ngāi Tūhoe, Tūhourangi, Scotland) looks up to the stars, to the celestial formations that have guided Māori ancestors through the Pacific for generations. In Māori astronomy, constellations come together in the form of Te Waka o Rangi, of which Matariki sits at the bow. In the Northen Hemisphere, Matariki is the shoulder of constellation Taurus. Having recently moved to New York, Paterson looks to the skies as a physical and spiritual anchor. His work embraces the idea of home extending across vast, celestial timeframes, as curator Dina Jezdić describes, blending ‘the vibrant, the sacred, and the ancestral.’ Each star is mapped directly from Hubble Telescope imagery, so that constellations are carefully scaled, honouring, in Paterson’s words, “the integrity of navigational stars and their meanings, but also my connection to home, from and within whakapapa.” Paterson’s crystal waka Guide Kaiārahi (2021), a 10-metre transparent waka pītau / carved war canoe has recently been reinstated in the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki’s forecourt pool, where it will spark curiosity and imagination over coming years.

In that stone, in that cyclone, in that leaf follows on from This Must Be the Place, the inaugural exhibition at our Onehunga flagship premises in March 2024, which considered place, belonging and cultural identity. We would like to acknowledge the support of Creative New Zealand - Pacific Arts Strategy towards Yuki Kihara and the Moata’a Aualuma Community’s newly commissioned work, and Tim Melville Gallery, who represents Star Gossage. Additional works from Kihara’s Tala o le tau: Stories from the weather (2025) series are currently presented in a group exhibition at Gus Fisher Gallery Te Whare Toi o Gus Fisher until the 30th of August.