Across the Earth: 100 Years of Colin McCahon

For McCahon, painting on loose canvas offered his works urgency – by eliminating painting’s more traditional stretchers and frames, he could confront his viewers more directly with the essence of the New Zealand landscape through raw material and his strikingly simple compositions.

-

Six days on the road with McCahon

September 10, 2019Hamish Coney writes for Newsroom as he takes a journey across New Zealand through the many exhibitions featuring works by Colin McCahon as we celebrate...Read more -

Across The Earth: 100 Years of Colin McCahon 'an Exhibition Not to Miss'

July 15, 2019Denizen has named Across The Earth: 100 Years of Colin McCahon 'an exhibition not to miss'. Read the full article here . The exhibition is...Read more

“I hoped to throw people into an involvement with the raw land, and also with raw painting. No mounts, no frames, a bit curly at the edges, but with, I hoped, more than the usual New Zealand landscape meaning.” – Colin McCahon on using loose canvas, 1972. [1]

To mark the centenary of Colin McCahon’s birth, Gow Langsford Gallery celebrates the preeminent New Zealand modernist with an exhibition of his paintings on loose canvas. Across the Earth: 100 years of Colin McCahon unites a collection of significant paintings that exemplify the artist’s distinctive treatment of the New Zealand landscape, and demonstrates the austere spiritualism endemic to his practice. Focussing on loose canvases of McCahon’s Muriwai period, the exhibition explores the immediacy of raw materials in the works of the giant of New Zealand painting.

By opting to leave a painted canvas unstretched, the canvas maintains its textile integrity - selvage and frayed edges are left visible, and a sense of physical movement remains with the hanging work. This is evinced in McCahon’s 1973 painting A Handkerchief for St Veronica, where the loose canvas directly relates to the folded cloth of the artist’s chosen subject. In the Fourteen Stations of the Cross, Veronica witnesses Christ bearing his cross ahead of his crucifixion. Seeing his distress she wipes his face with her veil (McCahon’s ‘Handkerchief’), and his visage is then miraculously imprinted onto the fabric.

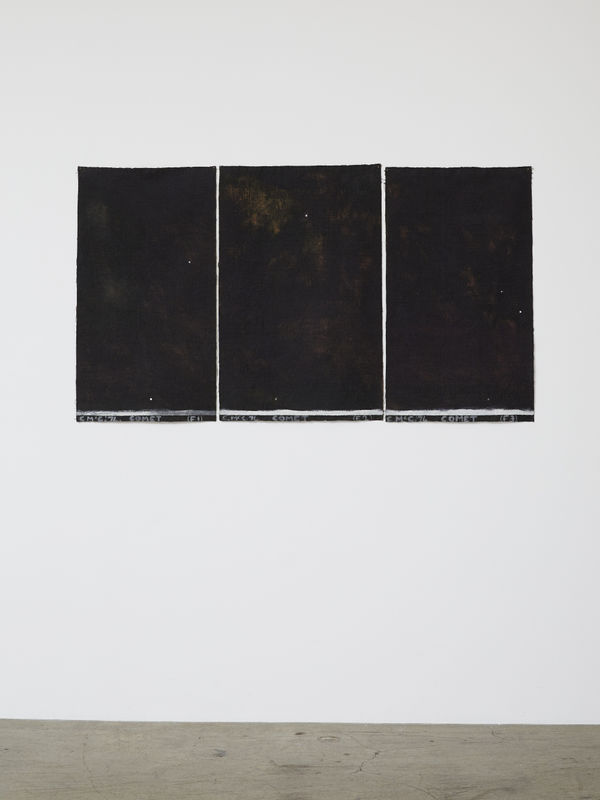

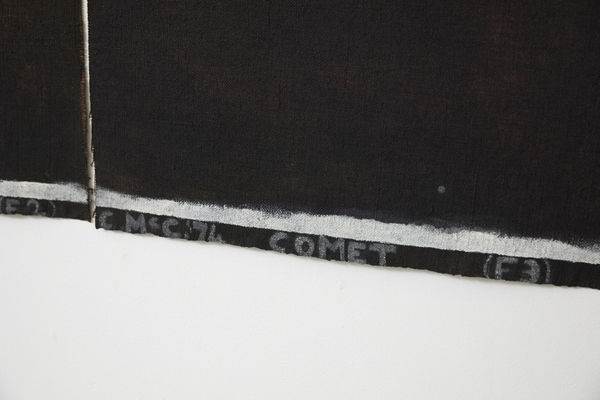

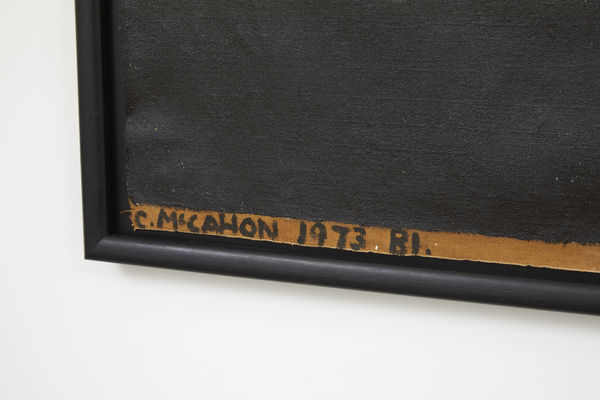

McCahon’s growing preference for loose canvas in his mature period parallels with the codification of his visual language. This junction is manifest in Comet (1974), and B1 (1973), both painted on jute at McCahon’s Muriwai studio. The jute’s rough texture takes on the immediacy of the ‘raw land’ McCahon sought to capture, while the expanse of the black-sand beach is condensed into sombre black and white bands. McCahon effectively frames the landscape of B1 with strips of the jute’s natural ochre colour, and in Comet he evokes the varying darkness of the night sky by allowing the jute (in places under painted with red) to bleed through thinly applied black. A white horizon glows low across the panels, guiding us from each to the next just as does the path of the comet above. Kokowai (1976) shares with Comet and B1 the infinite horizon of Muriwai, but also evinces the inclusion of Māori visual culture in his work of the period. Kokowai is the red ochre often used to paint wharenui, and is revered by Maori in oral history as the blood spilt by Tane when he split the sky father, Rangi, from the earth mother, Papatūānuku.

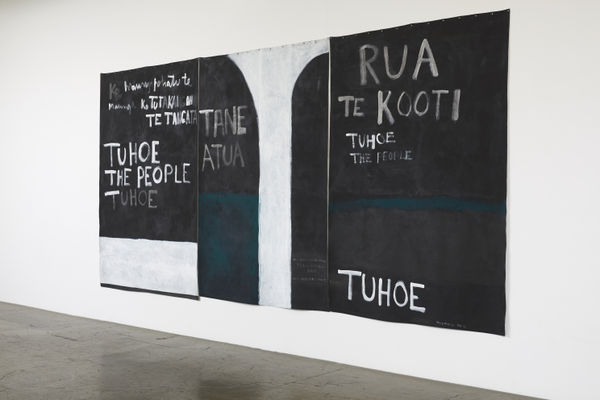

Across the Earth features the Urewera Triptych (1975), a seminal work in McCahon’s oeuvre which captures the majesty of the Urewera National Park and its people, Ngāi Tūhoe iwi. The epic three-panelled painting is an alternative to the Urewera Mural commissioned from McCahon to hang in the park’s Aniwaniwa Visitor Centre. The use of loose canvas in the Urewera Triptych recalls the famed flags designed and carried by Tūhoe prophets Rua Kēnana and Te Kooti, whose names appear on the right panel.

For McCahon, painting on loose canvas offered his works urgency – by eliminating painting’s more traditional stretchers and frames, he could confront his viewers more directly with the essence of the New Zealand landscape through raw material and his strikingly simple compositions.

[1] Colin McCahon, letter to Gordon H Brown, quoted in Gordon H Brown, Colin McCahon: Artist, 2nd ed., Reed, Wellington, 1993, p. 174